The evolution from silent films to talkies reshaped Indian cinema, igniting a revolution in storytelling through the power of dialogue. Amidst this cinematic metamorphosis lies a lesser-known hero, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, whose legal prowess played a pivotal role in the birth of Indian talkies.

In 1927, as the world marveled at the innovation of talkies with films like The Jazz Singer, filmmaker Ardeshir Irani envisioned crafting India’s inaugural synchronized sound production, inspired by the possibilities showcased in the 1930 film Show Boat. However, challenges loomed large, particularly concerning casting decisions that threatened to derail the ambitious project.

Enter Master Vithal, a revered figure in silent cinema, coveted for his talent and popularity. Yet, contractual entanglements with Sharada Studio cast a shadow over his potential involvement in Irani’s groundbreaking venture, Alam Ara.

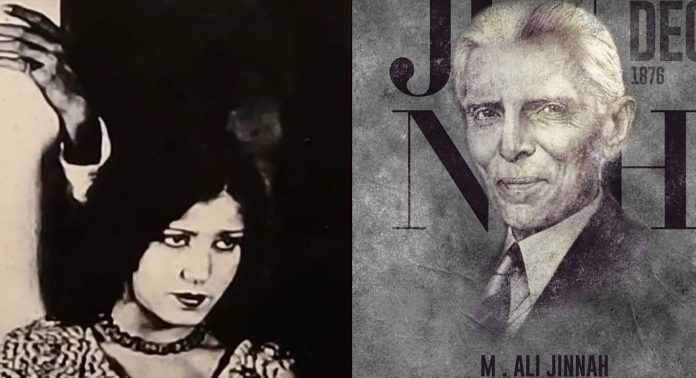

Sharada Studio’s legal action against Master Vithal jeopardized his participation in the film, prompting him to seek Jinnah’s legal expertise. Jinnah’s intervention cleared the path for Master Vithal to join the cast of Alam Ara, alongside luminaries like Zubeida and Prithviraj Kapoor.

Despite initial challenges, Alam Ara’s release in 1931 marked a historic milestone in Indian cinema, laying the foundation for its future trajectory. Jinnah’s role in this cinematic saga highlights his multifaceted contributions beyond the political realm.

Jinnah’s Vision for Cinema

Decades later, a letter penned by Jinnah in 1945 underscores his recognition of cinema’s potential and his encouragement for Muslim participation in the industry. In response to a young activist’s inquiry, Jinnah expressed his support for initiatives like Mr. Mahboob’s historical picture “Humayun,” emphasizing the ample opportunities for Muslims in the film domain.

This revelation sheds light on Jinnah’s enthusiasm for fostering cultural and artistic endeavors, even amidst the tumultuous political landscape of the time. However, despite his visionary outlook, successive Pakistani governments have largely neglected the country’s film industry, leading to its decline.

The state’s disregard for film education and industry support has contributed to the industry’s decline, contrasting sharply with Jinnah’s vision for a vibrant cinematic landscape. As Pakistan grapples with broader challenges, the legacy of Jinnah’s advocacy for cinema serves as a reminder of the untapped potential within the country’s cultural sphere.

The evolution from silent films to talkies reshaped Indian cinema, igniting a revolution in storytelling through the power of dialogue. Amidst this cinematic metamorphosis lies a lesser-known hero, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, whose legal prowess played a pivotal role in the birth of Indian talkies.

In 1927, as the world marveled at the innovation of talkies with films like The Jazz Singer, filmmaker Ardeshir Irani envisioned crafting India’s inaugural synchronized sound production, inspired by the possibilities showcased in the 1930 film Show Boat. However, challenges loomed large, particularly concerning casting decisions that threatened to derail the ambitious project.

Enter Master Vithal, a revered figure in silent cinema, coveted for his talent and popularity. Yet, contractual entanglements with Sharada Studio cast a shadow over his potential involvement in Irani’s groundbreaking venture, Alam Ara.

Sharada Studio’s legal action against Master Vithal jeopardized his participation in the film, prompting him to seek Jinnah’s legal expertise. Jinnah’s intervention cleared the path for Master Vithal to join the cast of Alam Ara, alongside luminaries like Zubeida and Prithviraj Kapoor.

Despite initial challenges, Alam Ara’s release in 1931 marked a historic milestone in Indian cinema, laying the foundation for its future trajectory. Jinnah’s role in this cinematic saga highlights his multifaceted contributions beyond the political realm.

Jinnah’s Vision for Cinema

Decades later, a letter penned by Jinnah in 1945 underscores his recognition of cinema’s potential and his encouragement for Muslim participation in the industry. In response to a young activist’s inquiry, Jinnah expressed his support for initiatives like Mr. Mahboob’s historical picture “Humayun,” emphasizing the ample opportunities for Muslims in the film domain.

This revelation sheds light on Jinnah’s enthusiasm for fostering cultural and artistic endeavors, even amidst the tumultuous political landscape of the time. However, despite his visionary outlook, successive Pakistani governments have largely neglected the country’s film industry, leading to its decline.

The state’s disregard for film education and industry support has contributed to the industry’s decline, contrasting sharply with Jinnah’s vision for a vibrant cinematic landscape. As Pakistan grapples with broader challenges, the legacy of Jinnah’s advocacy for cinema serves as a reminder of the untapped potential within the country’s cultural sphere.