While Oscar Wilde may have been correct that life imitates art more than the other way around, it seems to work the other way around in our regional theatre scene. You can find out how many TV dramas were released this year by doing a quick Google search.

That’s a lot of people who watch TV, and people who watch TV tend to fall into one of four socioeconomic groups, based on their household’s income and the number of televisions they own. This may cause you to question where you fall on the viewership spectrum, but the more pressing question is: where are all these dramas going?

Why is it that we can only recall a small number of names despite producing so much material? Star power is important, but it’s also important to note that recent Pakistani TV dramas have started to thrive on a small set of clichés and ideas, which has both strengthened the formula and stifled creativity.

Here’s to 2022 and the hope that the producers of dramas will finally be able to leave these five things behind, quietly and shamefully.

Abusing men can be forgiven easily.

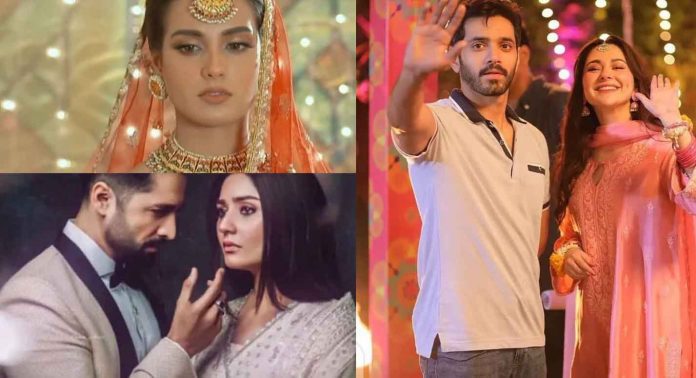

TV shows like Kaisi Teri Khudgarzi, Habs, and Wehshi give the bad guys a happy ending as if depicting abusive husbands and father figures wasn’t enough. For all the slapping, swearing, and yelling that goes on in the show, it only takes one “honest” good deed for them to be saved.

However, the female counterpart has no way out if she is self-centered, conceited, or greedy. When they make it through the harassment, they aren’t even helped. For instance, instead of being portrayed as a victim in need of support after surviving a rape attempt, Aietbaar’s Xarnish Khan spends the entire show defending herself in front of her husband and feeding his fragile ego so he doesn’t feel hurt that someone else “touched” his wife.

Contrary to popular belief, this casts reality in stark black-and-white terms. These cliches encourage you to keep going through the abuse because the men who do it to you in real life are good at heart and just having a bad day.

Saas is evil, and Bahu is weak.

The villainous Saas and weak Bahu plotlines, which have been around for as long as I have, have got to be the first to leave screens this year. TV shows have used this trope so often that it has become a stereotype, if not an expectation, of viewers, regardless of whether or not it originally reflected society at large.

Your mother-in-law’s understanding of your desire for privacy and acceptance in your new home, as well as her recognition of your devotion to your husband, should come as no surprise. Nonetheless, it shouldn’t come as a shock if she has problems with you seeing your family and interacting with them on an equal footing. The daughter-in-law, like Hala (Hania Aamir) in Mere Humsafar, does not have to keep her emotions in check and cry constantly.

The women in both Mere Damaad and Meray Humnasheen are shown subtly encouraging their female friends to be a little intrusive or they will lose “authority” in the house. Everyone has overheard or participated in conversations like these, and now is the time to strike a balance, if not completely abandon the use of malicious saas and weak bahus.

Fabrication.

Although Sang-e-Mah, starring Atif Aslam, was well-received by audiences in 2022, the show was criticized for its inaccurate portrayal of Pashtun culture and language. Some viewers of Ahsan Khan’s Meray Humnasheen this year felt the same way, claiming the producers could have filmed the same drama without showing naswar and guns in the hands of every Pashtun character.

Before casting actors who don’t come from a specific background, producers should do their homework and give them some coaching. Similarly, after Joyland was criticised for featuring a trans actor and pushing the LGBTQ+ agenda, viewers on social media pointed out the deadly consequences of portrayals of trans characters in comedic roles in TV and film.

Fourth, marriages between relatives.

No explanation is necessary at this point, but it appears that the entertainment industry in our region is fixated on ignoring science and consciousness. Evidently, the people who make our TV shows don’t care about the large amount of peer-reviewed research that shows that cousin marriages make children more likely to get diseases that are passed down through their genes.

According to the National Library of Medicine, there is a higher risk of passing on recessive disorders through cousin marriages, which can lead to conditions as varied as primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), thalassemia, and Tay-Sachs disease, all of which can have devastating effects on patients.

Adultery.

To normalise infidelity as an escape in relationships that “everyone needs once in a while” is to do one thing: demonstrate how infidelity and adultery are endemic to human relationships and a leading factor in destroying marriages.

Many such dramas, including Dushman, Meray Hamnasheen, Wehem, and Habs, have delicately navigated the topic of men having affairs with modern, jeans-wearing women while their “nice” wives, who wear shalwar kameez, remain submissive. Cheating is not necessarily associated with a modern woman who is “ruining” someone’s family, so perhaps the idea can be carried out less frequently than it usually is.

Additionally, this year saw a number of shows that were praised and discussed for their ability to challenge societal norms and break with stereotypes. Some shows, like Yumna Zaidi’s Bakhtawar, Ramsha Khan’s humorous Hum Tum, and Hadiqa Kiani’s poignant Pinjra, are taking a stand for what is right rather than what is popular.